Table of contents

Atomic Inclusion

The first step on our road to Universal Synchronous Composability is “Atomic Inclusion.” Remember from our terminology that atomic means “all or nothing” and inclusion means transactions are sequenced for a rollup. Together, atomic inclusion means that transactions are guaranteed to either be sequenced for multiple rollups or none at all.

when creating new history for both rollups at once, the shared Sequencer can exercise some extra power by atomically “linking” history on the two rollups to each other. The Sequencer produces sequences for each rollup simultaneously, and ensures that either both confirm or neither confirms - James Prestwich

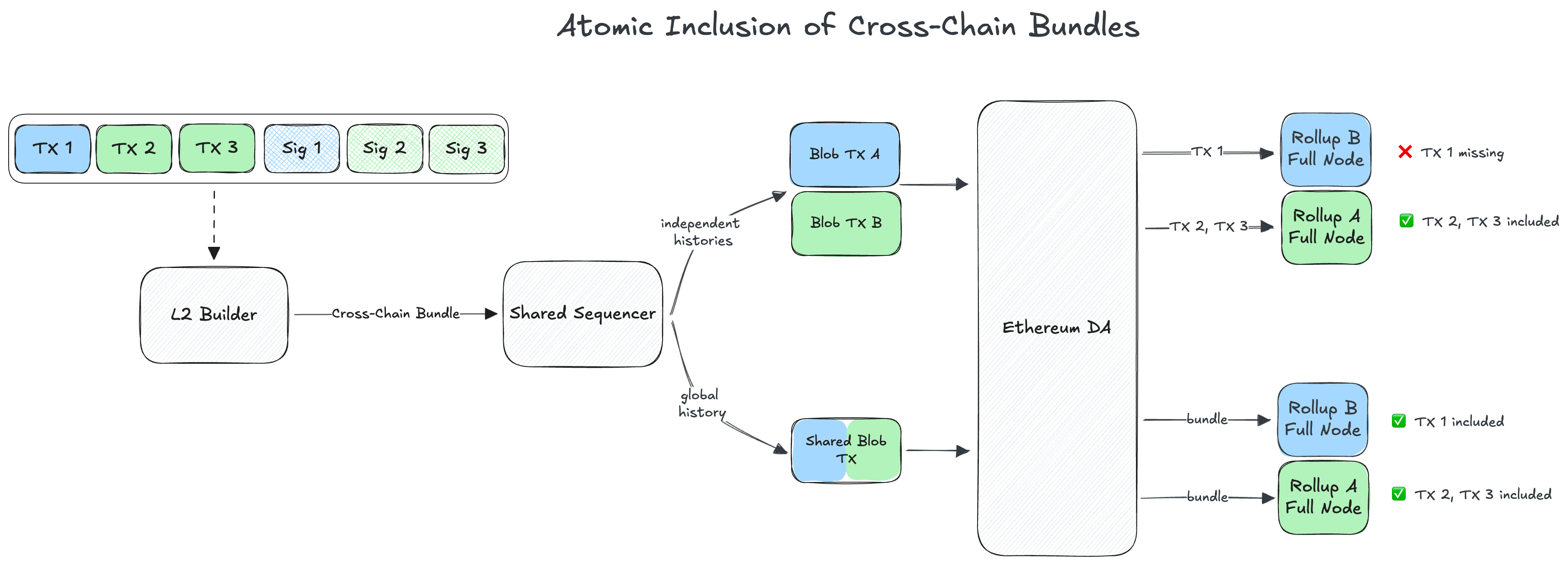

Classically, rollups have a single dedicated sequencer that independentally writes their rollups history by producing sequenced L2 transactions in the form of blobs. When the sequencer is responsible for sequencing multiple rollups, they are called a “shared sequencer.” The superpower of shared sequencing comes into play if the shared sequencer creates a singular global history for multiple rollups.

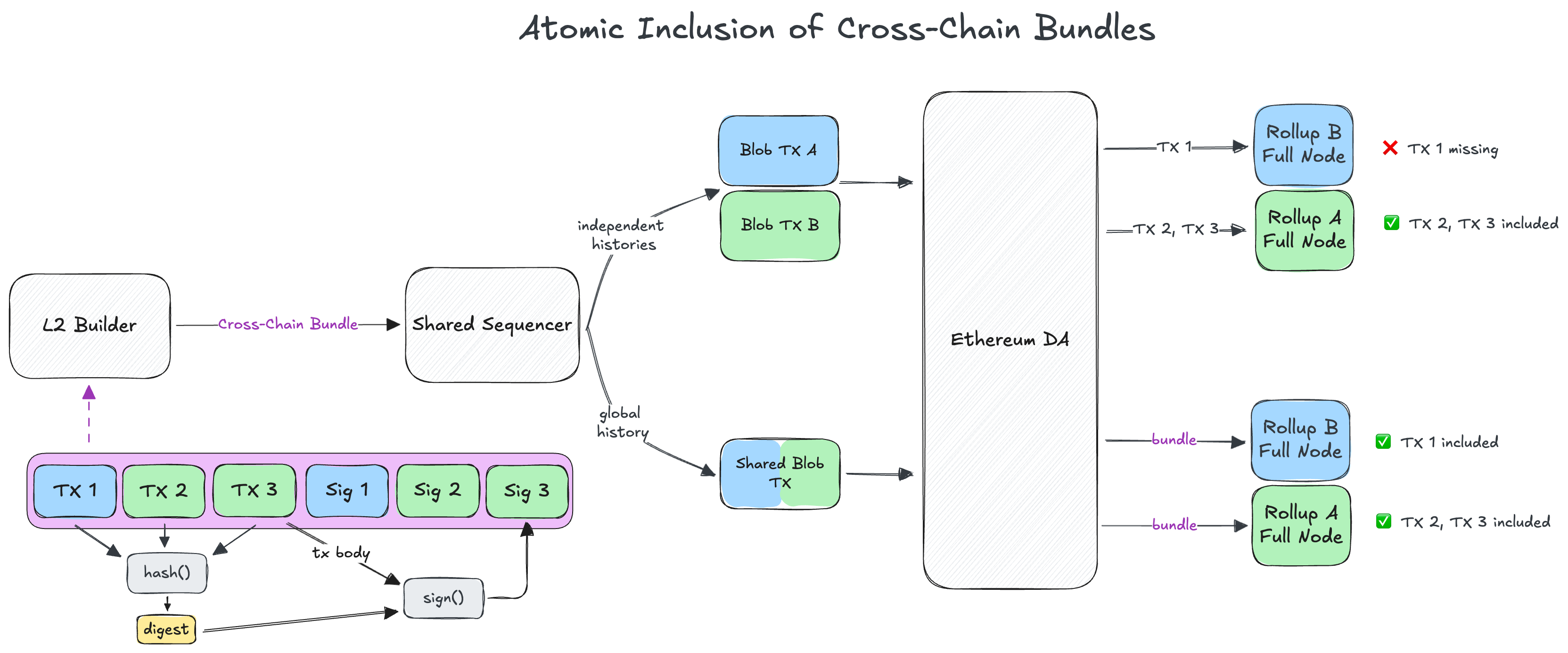

In the image above, the top-right depicts a shared sequencer posting independent sequences to the DA layer and as a result it’s trivial for them break atomicity (i.e., they decide to exclude \(TX_1\) but include \(TX_2\) and \(TX_3\) as shown). It’s possible to use reputation and collateral to disincentivize this behavior but we can do better.

In the bottom-right of the image, the shared sequencer commits to a single global history by including the transactions within a shared blob transaction, meaning the blob encode both rollups’ sequences of transactions. When deriving their states, both rollup full nodes will read from the same blob, guaranteeing a consistent view of the bundles.

Preventing unbundling

While shared sequencing is necessary, it’s not sufficient to provide the atomic inclusion guarantee. What happens if the shared sequencer unbundles the transactions before posting the shared blob (i.e., they remove \(TX_1\) again)?

Ben Fisch proposed a solution to prevent this type of unbundling. As depicted in the bottom-left of the image, each transaction’s signature includes a commitment to the entire bundle (the bundle hash). This means unless the full bundle is posted to DA, the rollup node would not be able to verify the signatures of any individual transactions within the bundle. This is sufficient to guarantee that either the whole bundle is included as-submitted or none of the transactions in the bundle will be considered valid, giving us the atomic inclusion guarantee.

In other words, if \(TX_1\) is left out but \(TX_2\) and \(TX_3\) are included, the rollup node will simply discard \(TX_2\) and \(TX_3\) for failing the signature check. Note this requires small modifications to the rollup’s derivation but so does parsing shared blobs.

To summarize, by using the shared sequencer to sequence multiple rollups we’ve achieved synchronous (because they are sequenced at the same height) atomic (bundle is as-is or not at all) inclusion (transactions are included in the rollups’ history).

Limitations

While atomic inclusion is a great first step towards USC it lacks some desirable properties, particularly execution. Atomic inclusion only guarantees that transactions are included in L2 blocks but doesn’t provide guarantees about them successfully executing (i.e., does it revert or not) or give guarantees about the resulting rollup state (i.e., state after executing the transaction at position X within the L2 block).

From a shared sequencer’s POV they can assure themselves about the rollup’s state after execution since they were part of the block’s construction. However, it’s another thing to convince other parties (i.e., users and smart contracts) about the rollup’s resulting state. So how does this limit the utility of atomic inclusion?

Example

Imagine Alice wants to perform a cross-chain transfer by burning tokens on \(R_A\) and minting on \(R_B\). Atomic inclusion guarantees that \(TX_A\) and \(TX_B\) will both make it into the respective rollup blocks. However, since \(TX_A\) or \(TX_B\) are fallible transactions (they can revert), we can end up in an undesirable state.

For example, \(TX_A\) could revert due to the user spending all their tokens in a previous transaction \(TX_{A-1}\). If \(TX_B\) proceeds to mint tokens, the token’s accounting is ruined. This example demonstrates that atomic inclusion alone cannot guarantee the properties needed to safely perform actions like cross-chain transfers.

| \(TX_A\) succeeds | \(TX_B\) succeeds | Result |

|---|---|---|

| ✅ | ✅ | Happy case - atomic burn and mint |

| ✅ | ❌ | Alice lost her tokens |

| ❌ | ✅ | Token supply inflated |

| ❌ | ❌ | Happy case - atomicity held |

The issue is that when executing \(TX_B\), \(R_B\) is not aware of the state of \(R_A\) to know if \(TX_A\) had succeeded or not. For this to be safe, the contract on \(R_B\) needs assurances to either guarantee the state of \(R_A\) is correct (cryptographic safety) or disincentivize bad behavior from the shared sequencer (cryptoeconomic safety).

In the next section we’ll learn about atomic execution and how it addresses this issue. > Step 2 - Atomic Execution